(an alternate version of an article written for Dunmanway Doings Volume VI – 2014)

Gordon J.R. Kingston

*

It’s early morning. The earth breathes out a heavy mist and the dew gathers on the spines and the cobwebs on the furze. The fog seems to hang over Lough Atarriff, leaving a void that mirrors the shape of the surface below. A car engine sounds in the distance. You think that it’s just you (and whatever creeps and crawls unseen through the wet grass) that’s moving. But you’re not alone. Four grey figures stand, one fallen, in relief against the whiteness, as if all else; hill, valley, present, past, has been carved away from around them. They are static, but filled with a hovering tension, in which verticality and circularity combine; to form the illusion of movement, or life, or the quality of art.

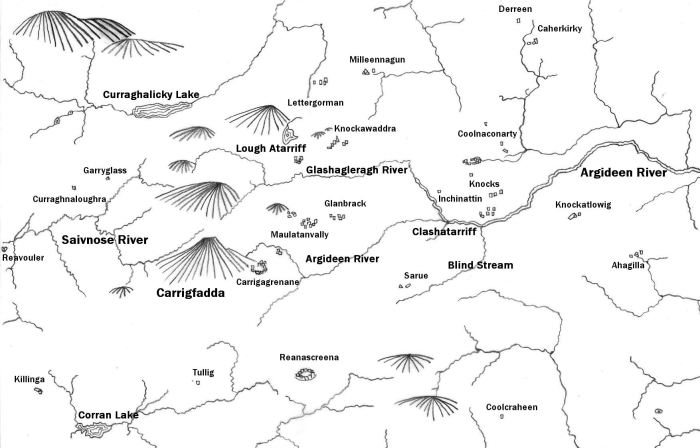

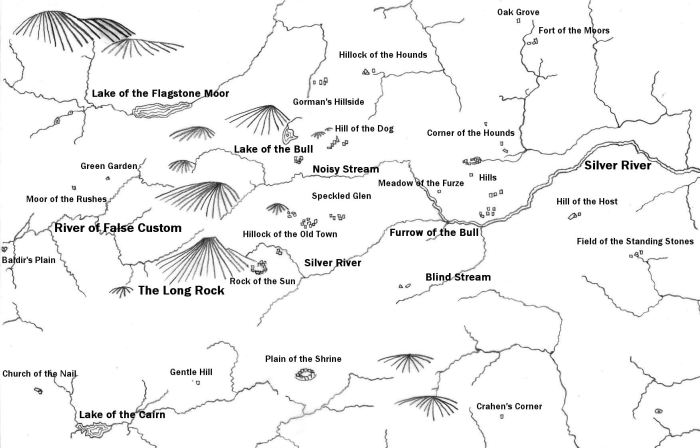

The stone circle at Lettergorman is set high on a plateau, near the southern town-land border with Knockawaddra and about 170 metres above sea level. To its southwest are the hills of Maulatanvally and Carrigfadda, and to the west; Coomatallin. The ground crests to the circle‘s north, the lip of a basin for the waters of Lough Atarriff, before falling and spreading out to the east as the Argideen river valley.

Over one hundred such open structures survive in southwest Ireland, mostly in the wilder, hillier areas; part of a regional Bronze Age culture that also included stone rows (of varying lengths), boulder-burials, monoliths, cairns and stone groups [1]. Lettergorman circle, itself, is part of a distinct group of fourteen remaining examples in the Rosscarbery area; roughly bounded by Clonakilty to the east, Leap and Drinagh to the west, and to the north by the hinterland of Carrigfadda [Table 1].

Morphology

Lettergorman circle is comprised of five stones. The two tallest uprights were set at the northeast, and a large recumbent block at the southwest. On either side of the recumbent, and between it and the two tallest stones, two further uprights of intermediate height were placed opposite each other; resulting in a roughly circular, symmetrical structure, with an axis of symmetry that bisected the recumbent to the southwest, and the gap between the two tallest stones to the northeast. This is a standard architecture for the stone circles of southwest Ireland, whatever their diameter, or however many stones they contained.

All the stones at Lettergorman were placed along the circle’s circumference. Often, particularly in stone circles that contained more than five stones (usually referred to as “multiple-stone circles”), the two stones set opposite the recumbent (the “entrance stones” or “portals”) were placed radially, as if to emphasise a valid access point. In the Rosscarbery group, six of the eleven circles with identifiable portals have this feature. At Carrigagrenane South, a further stone was set outside each of these radial uprights, forming a short passageway.

The northern portal at Lettergorman, heavily and diagonally scored, is fallen inwards. It was measured in a survey by Sean O’Nuallain at 1.60 metres high, 1.00 metres wide and 0.30 metres thick, and presumably stood to a similar height as its partner when upright (1.40 metres) [2]. Both these stones are substantial grey slabs which, in the warm light of a summer’s day, can sometimes bleed out an unexpected colour; a soft pink or a pastel blue. Their tops are gently peaked, like the hilltops around them.

The maximum width of the circle was measured by O’Nuallain at 2.75 metres and its axis of symmetry, northeast to southwest, at 3.05 metres. On either side of this axis are the two, intermediate height, flanking stones. The southerly stone is complete; topped like the portals and wide, but the northerly seems to have broken near its base, leaving just a thin slice standing.

There is also a wedge loose on the outer base of the tall recumbent, or axial stone. This stone stands 1.0 metres high, 1.70 metres wide and 0.60 metres thick, with a deep grey interior, a flat, level top, and a shallow exterior ledge. The ledge is a feature unique in this group to Lettergorman, although there is another five-stone circle with a similar, albeit lower, axial ledge; north of the road between Coppeen and Crookstown, at Knocknaneirk.

Six axial stones in the Rosscarbery group have similar flat, level tops, while the top surfaces of four others are also perfectly even, but have an interior bevel, or slope. These latter bear resemblance, not so much to a table, but to an old school-desk, or lectern. Contrarily, the axial stone at Reenascreena narrows gradually to a ridge, more like the side of a cushion, and at Maulatanvally it becomes thin and uneven. All these stones, when viewed along their circle axis, had a horizontal upper line. As to the others, the original disposition of the stone at Ahagilla is uncertain, and the stone at Garryglass is gone [Table 3].

Interestingly, four of the axial stones are dog-eared, with a bevel that extends from their top surface to a point part-way down their northern side; at Ballyvackey, Bohonagh, Carrigagrenane South and Lettergorman. Could this have been functional or, perhaps, a form of lithic signature mark? Lettergorman doesn’t have the interior bevel common to the other three, and Templebryan, which does, doesn’t have the northern bevel. If the local imperative was to have an even top surface, regardless of slope, then the northern bevel may indicate that a connection, beyond the group archetype, existed between these four circles.

There is also a pronounced concave area on the uppermost, interior edge of the axial stone at Lettergorman, but the only stone with a similar feature is that at Ahagilla (to which the previously mentioned reservation applies). It would seem of a height and shape to rest a tall object, or a head, but could as easily be a naturally occurring depression.

One more stone is present, just outside the five-stone circle. A brilliant white quartz block, 1.30 metres at its maximum. It rests between the southern flanker and the axial stone, and roughly indicates, if its position is original, a stone group across the way at Maulatanvally [RG2]. Three of the four stones in that possible four-poster are also composed of the same material. Quartz is a common accessory in the Bronze Age monuments of this region and it accompanied at least four of the fourteen circles in the Rosscarbery group.

Excavations at Rosscarbery group circles

Three of the Rosscarbery group circles have been excavated; Drombeg, Bohonagh and Reenascreena, and single deposits of cremated human bone were found in unmarked pits in each. There were some variations in the methods of committal.

At Drombeg, the main burial, with associated broken pottery, was located in a pit that was slightly east of centre. The circle’s axis of symmetry bisected the space between this and another pit that contained a small deposit of charcoal and cremated bone [3]. A tightly-packed gravel floor had been laid in the circle interior, above the pits. Charcoal on the broken pottery vessel provided a date range of 1115-791 BC for a deposit that was almost certainly concurrent with the monument’s construction [4, 5].

In contrast, at Bohonagh the pit was placed centrally and on the axis of symmetry, and the bone fragments were deposited cleanly, with no evidence of elaboration [6]. Soil appeared to have been purged from the circle interior during construction, and before the burial was deposited [7]. A radiocarbon result of 1371-1055 BC was provided from a sample of this bone, in line with a range of 1259-1024 BC for bone from the nearby boulder-burial [8].

At Reenascreena there was also a central pit on the axis of symmetry, but it contained only soil. The burial was positioned north of centre, and involved the placement of some of the larger bone fragments beneath a lump of shale at the bottom of a pit and, possibly, the adhesion of the remainder, mixed with charcoal, to the pit sides [9]. A radiocarbon result of 1000-835 BC was obtained for this charcoal. A further sample, found outside the perimeter, gave a date range of 1253-943 BC for the construction of the circle’s eastern bank [10].

Charcoal flecks were found throughout the lowest layer of the circle interior, and in the ditch around it, but the greatest clusters were located in the northeast section and near the portals. This area of ditch had been worn down, presumably by regular use, and repaired [11]. Dark areas of charcoal-peppered turf were also present outside the portals at Drombeg and Bohonagh [12, 13].

Relationship to other features in the wider monument culture

While the interior space of each circle may have been charged with meaning to its builders, the emphasis on their axes of symmetry, and their consistent orientation from east/northeast to west/southwest, suggests that there was also something powerful outside it. Something that meant that the whole structure, in common with the local wedge tombs, stone rows and the long axes of monoliths, had to be lined up in that direction. William O’Brien has argued, persuasively, that the orientation of much of this monumental culture may have been influenced by a belief in an otherworld that lay beyond the western seas; a distant land of the dead, reached by the setting sun [14].

Studies made of the orientations of groups of local monument types have shown that they had a number of differences in emphasis, within the overall east/west structure, and that, if valid, the belief could have existed as either part, or all, of a monument’s orientation formula. If part, for instance, the structure may have provided a contact with the otherworld, but subject to another focus; such as a sacred hill, or a hill as gateway to the otherworld, a spring, or a spring as the same, a limiting position of a solar or lunar deity, a star, or something else entirely. If all, then no more would have been needed for its builders than a convenient position and a roughly east/west orientation for an axis.

From the vantage point of Altar wedge tomb, for example, the sun sets into Mizen peak on the 5th February and the 3rd/4th November of every year; around or about the festivals of Imbolc and Samhain. These are what are termed cross-quarter days; the mid-points between the equinoxes and the winter solstice, and, historically, have signalled the beginning of Spring and the beginning of Winter. The tomb’s orientation, taken from back-stone to opening, directly indicates both the peak and the events.

However, of the nine further wedge tombs that were examined on the peninsula, no other was found to be oriented on this, or any other, hilltop and only two others, or possibly three, had an orientation in the rough range of sunset on the cross-quarter days. All were facing south of west, but four of the nine had orientations that were outside the furthest southerly position of the sun [15].

There was more consistency in the Cork/Kerry stone rows. In a study by Clive Ruggles, a significant number were found to be oriented, along their direction of indication (as determined by the gradations of stone height along their line), not only on particular hills and distant horizons, but on areas where the moon set and rose. Both northeast and southwest were equally represented as directions of indication [16].

Relationship to other features in the Rosscarbery circles

A hill can easily be identified as a possible focus. Observing a link with bodies such as the sun, or moon, is more difficult. We can only assume that the horizon would have been indicated, rather than the position of a heavenly body in the sky, and that ritual significance might have been attached to certain events, or times of the year. Rising and setting positions change daily and, in the longer term, the limits of these positions have also changed. To get around this latter problem, the concept of declination is used to assign a value to the paths of the sun, moon and stars [Table 4].

Lettergorman circle has an open view, along the length of its plateau, to the southwest, and its axis of symmetry is aligned, in this direction, to a saddle between the hills of Carrigfadda and Coomatallin. Specifically, Jon Patrick found it to be aligned to a horizon point with a declination of -24.3 degrees; just half a degree, or one solar diameter, south of the declination of winter solstice sunset circa 1000 BC [17].

Of the ten measured circles in the Rosscarbery group, four have axes of symmetry that indicate to within one degree of either the Late Bronze Age midwinter sunset, or the equinox sunset. Both Lettergorman, with a saddle, and Drombeg, with a notch, are also oriented on features that might, like Mizen peak and Altar, offer support to the intentionality of this focus. However, the alignment at Drombeg, despite its fame, is inexact.

Due to the contraction, over time, in sunset limiting positions, the Late Bronze Age midwinter sun would not have set where we see it now, but at 0.80 degrees, or over one and a half sun-widths, south of the circle’s projected axial line. More pertinently, the declination of the horizon notch, at -22.9 degrees, suggests that the sun could only have entered it about a fortnight before or after the solstice, but not during [18].

At Lettergorman, in contrast, this same process has resulted in the limiting position moving a short distance north and away from the circle’s projected horizon point. But its wider, shallower, basin has also meant that, on a clear evening, the midwinter sun sets to much the same effect as it would have long ago. This is not to say that the event was not deliberately, albeit roughly, indicated at Drombeg, but that the notch was indicated more precisely, and that the present picture, where the two elements are in conjunction, is not accurate.

The western declinations gathered by Jon Patrick and Peter Freeman, and, later, Clive Ruggles provide a range for the Rosscarbery group of just over thirty-seven degrees; from -34.13 degrees at Templebryan to +1.22 degrees at Knocks North, with one degree of error allowed on each side. Outside the four possible solar indications there is one possible lunar orientation; at Carrigagrenane South and one, like the stone rows, that directly indicates a hill; Maulatanvally and the lower, northern ridge of Carrigfadda [Table 5]. These are both isolated results, however, and the significance of Drombeg’s notch, or Lettergorman’s saddle, or even the setting point of a star, could equally be mooted.

In Ruggles’ overall study, he found thirty-one circles with indicated western declinations that were ranged between -36.00 degrees and +10.20 degrees, but only two with an orientation within one degree of the winter solstice sunset, and three within one degree of the equinox sunset. Three circles roughly indicated the southern minor moonset limit and two, the southern major limit. Four circles had bearings within one degree of a hilltop [19].

Patrick and Freeman’s results were also derived from thirty-one circles, with indicated western declinations ranging from -34.13 degrees to +7.76 degrees. Two had orientations within one degree of the winter solstice sunset. Three were oriented within one degree of the equinox sunset, and three within one degree of the southern minor moonset limit. They concluded that the solar and lunar results that they identified to the west/southwest, although imprecise, were “indicated more often than by chance“, but found no statistical significance in the measurements that they took in the opposite direction; from the axial stone back through the centre of the portals [20].

Although the overall results are, admittedly, murky, and conclusions drawn from a smaller (albeit geographically confined) sample could be disputed, a cautious case might be made for the significance of the Rosscarbery results. Over half of Ruggles’ and Patrick and Freeman’s sunset indications, for solstice and equinox, are found within the group. In addition, while just 11% of the Rosscarbery declination range is covered by the solstice and equinox values, those proportions contain 40% of the measured circles. The two collections have been combined, in Table 6, to demonstrate the extent of the solar cluster around the Rosscarbery area.

Evidence for the intentionality of the one moonset orientation is weaker. Carrigagrenane South is the only local circle to indicate the southern major limit and the alignment may well be coincidental. As may the indication of the hill from Maulatanvally. Although exact, it is unique in the Rosscarbery group and would be impossible to prove as deliberate.

Relationship to other monuments

If you stand at Lettergorman it is just possible to see the stones at Glanbrack, but easier to pick out the one free-standing quartz pillar at the Maultanvally stone group. Despite the close proximity of (and ease of reference between) many of these sites, particularly on the eastern outskirts of Carrigfadda, few are truly intervisible. Even the closer examples can be hidden from each other; whether by the edge of a hill or a slight rise in the ground, or the limitations of an eye.

The only indicated relationships in the area are between Lettergorman and the Maulatanvally stone group, and the stone row at Knockawaddra West and the same group.

The indication from Lettergorman relies, as referred to earlier, on the large quartz block beside the circle, but this boulder is without obvious support and its position may not be original. Even if an original feature, its placement may not have been intentional in this respect. The indication from Knockawaddra is more concrete. The bearing of the row, southwest to the stones at Maulatanvally, can been calculated to 212.25 degrees over 1.79 kilometres (+/- 5 metres in site position), comfortably within Clive Ruggles’ indicated azimuth range of 213 +/-2 degrees [21].

Although it is possible to link a number of the other Rosscarbery area circles and stone groups with straight lines [Table 7], such paper results should be treated with caution. The only remaining visible steering point is at Maulatanvally; “Meall an tSean Bhaile”, or “the hillock of the old town”. Standing by the stones there, even now, you can see across to the circle at Lettergorman, down to Glanbrack and, but for a tall growth of evergreens, northeast to the Knockawaddra row, along its line of indication.

Discussion

The most frequently-asked questions about these circles relate to their function and meaning. What were they used for and how were they used? Was the circle at Lettergorman sepulchral; a tomb erected after the death of some local notable, or was it a ritual structure that just happened to contain someone’s remains? If the latter, what form would a ritual have taken there?

The sepulchral possibility should not be dismissed out of hand. Issues such as the careful preparation found in the excavated circle interiors, the privileging of their axes of symmetry, or the fact that all burials were single insertions, and of fragments only, may also have been part of a necessary funerary context; like an Egyptian pyramid for a local king.

If there is evidence for ritual use, it is in the charcoal concentrations outside the portals at Drombeg, Bohonagh and Reenascreena, and the wear and repair of the portal area at the latter; these signs of ongoing use imply a function that required the living. In such a scenario, the single insertion of cremated bone would have been dedicatory, to appease a deity and, if not conserved remains, the result of human sacrifice.

The motive behind the monuments’ orientation is also important. Did the circles look in a general direction, or did they look to an object within that direction? Around Carrigfadda, several sites, with noticeable variations in orientation, are all settled within a short walk of each other. It could be argued that a circle, as a simple tomb, would need no more than a rough westerly indication, but it might also be expected that all examples within easy visual reference of each other would tend to line up in much the same direction, and this is not the case.

If each circle were to be considered, instead, as a dedicated ritual structure or, at the least, a tomb with an ongoing ritual function, it opens the possibility that such dedication, or devotion, to a specific deity, may have acted to determine the direction of indication. Thus, while the consistent orientation range, of all examples, could be framed in terms of a reaching out in the direction of a western otherworld, the individual projection of each circle, within the east/west culture, might have looked to their own particular deity, or object of contact.

If so, and if we accept the relevance of the events, the possibility that four of the circles might have shared in devotion to the same deity is suggested by the solar clusters of the greater Rosscarbery area. Similarly, the possibility that each circle might have been dedicated to one deity, alone, is suggested by the close proximity of the several Carrigfadda examples. The sunset orientation at Lettergorman implies that it was the circle of a sun-god, with a festival at midwinter.

Traces of power linger in T.F. O’Rahilly’s description of the Celtic version; not just sun-god, but the god of thunder and lightning, the lord of the otherworld and the ancestor of all men. He was Aed (fire), Eochaid Ollathair (Eochaid the great father), Goll (the one-eyed) and Balar (the one-eyed) [22]. Balar was associated in legend with the Mizen and therefore, by extension, with sunset from Altar wedge tomb. In a similar fashion, Lettergorman’s location may have been significant for many years before the circle’s construction; known for its conjunction of lake, plateau, winter sunset and saddle.

The form that might have been taken by a local solar ritual, or midwinter festival, is lost to us, but parallels may be drawn, tentatively, with activities in similar structures elsewhere. For this purpose, it is helpful to ignore the circles’ position in the wider circular idiom and to think of them, instead, as an evolution in the particular Bronze Age monumental culture of West Cork. Structurally, this was an evolution that ensured the retention of the east/west orientation of the earlier wedge tombs and stone rows, but prioritised, within it, a physical boundary and a distinct, recumbent stone.

The axial stone at Lettergorman, like ten of the twelve that survive in the group, is a block with an even, altar-like, top surface. It is distinguished from all other stones in the monument by its placement on the axis of symmetry and by its horizontality, but it acts with them as a boundary to differentiate the space inside. We have also seen that traces of ongoing activity at the excavated circles were concentrated just outside the portals, not inside, and that elaborate care was taken with the preparation of the circle floor at Drombeg and Bohonagh. At Reenascreena the circle boundary was further emphasised by an exterior ditch.

Strong parallels can be made, for instance, with Greek sanctuaries of the same era. At their most basic level they required only an altar and an open, sacred space, demarcated from the physical plane by a boundary [23]. The sacred space, a sort of embassy in the human world, was regarded as the property of the relevant deity, and the altar, which was used to communicate with it via sacrifice, served as a threshold to the Grecian otherworld.

Belief and the natural landscape should not, or probably did not, always need a built chaperone, but it could be argued that this was a model that was ideally suited to its particular form of ritual. If the stone circles, as similar structures at root level, performed a similar function, then we might expect sacrifice or offering, using the interior of the circle and the surface of the axial stone, to have been fundamental to the way in which they were used.

Blood-sacrifice, in ancient Mediterranean ritual, was usually of an animal, with bulls and cattle as the highest status gifts [24]. Typically, the offering would be led in a procession that culminated in it being bled to death within the sacred space. Its vital fluid would be gathered in a vessel and then sprinkled over the altar. Crucially, following invocation, the deity that possessed the space; sun-god, or otherwise, was believed to take part in the ritual [25].

Lough Atarriff, or “the lake of the bull”, was probably named for its zoomorphic, double-peaked shape, but stories persist, to this day, of a monster living under its waters. Think, perhaps, of the horned aspect of an ancient god, before or after invocation, or the final destination of a bovine myth or sacrifice. As if in corroboration of the latter image; Clashatarriff, “the trench (furrow) of the bull”, is located on the course of the Argideen river, a short distance east of the circle.

Intriguingly, cup marks on three of the Rosscarbery group axial stones could have had relevance as fluid containers. As could the ledge on the exterior of the stone here, in clear sight of the setting winter sun. The axe symbol at the other solstice circle, Drombeg, might even be seen as a totem of the final link between two worlds; the sacrificial blade [26].

*

When they came to the place of which God had told him, Abraham built an altar there, and laid the wood in order, and bound Isaac his son, and laid him on the altar, upon the wood. Then Abraham put forth his hand, and took the knife to slay his son.

Genesis 22; 9-10.

*

Who moans with that moan

of an ox, huge and sad?

Mother, it’s the moon, it’s the moon

In the courtyard of the dead.

Yes, it’s the moon, the moon

With its crown of gorse

That dances, dances, dances

In the courtyard of the dead!

From ‘Dance of the Moon in Santiago’ by Federico Garcia Lorca [27].

*

Table 1

| Townland / Name | No. | Classification | Latitude | Longitude | |

| GPS +/- 5m | |||||

| RC1 | Ahagilla | 3525 | Multiple Stone Circle | N 51.64097 | W -8.96327 |

| RC2 | Ballyvackey | 43 | Multiple Stone Circle | N 51.63327 | W -8.94834 |

| RC3 | Bohonagh | 44 | Multiple Stone Circle | N 51.58056 | W -8.99964 |

| RC4 | Carrigagrenane North | 67 | 5 Stone Circle | N 51.64144 | W -9.07090 |

| RC5 | Carrigagrenane South | 47 | Multiple Stone Circle | N 51.63709 | W -9.07810 |

| RC6 | Drombeg | 52 | Multiple Stone Circle | N 51.56457 | W -9.08705 |

| RC7 | Garryglass | 55 | Multiple Stone Circle | N 51.65463 | W -9.12373 |

| RC8 | Glanbrack | 74 (207) | 5 Stone Circle (& Pair) | N 51.64810 | W -9.05331 |

| RC9 | Knocks North | 57 | Multiple Stone Circle | N 51.65949 | W -9.01325 |

| RC10 | Knocks South | 58 | Multiple Stone Circle | N 51.64749 | W -9.00848 |

| RC11 | Lettergorman | 79 | 5 Stone Circle | N 51.65857 | W -9.06702 |

| RC12 | Maulatanvally | 60 | Multiple Stone Circle | N 51.64614 | W -9.06488 |

| RC13 | Reenascreena | 61 | Multiple Stone Circle | N 51.61781 | W -9.06328 |

| RC14 | Templebryan | 62 | Multiple Stone Circle | N 51.64315 | W -8.88337 |

| RG1 | Lettergorman | 85 | Four Poster | N 51.67356 | W -9.05969 |

| RG2 | Maulatanvally | 921 | Anomalous Stone Group | N 51.64850 | W -9.06907 |

| RG3 | Tinneel | 926 | Anomalous Stone Group | N 51.59238 | W -9.01940 |

| Knockawaddra West | 157 | Stone Row | N 51.66209 | W -9.05525 | |

| Carrigfadda Eastern Peak | Mountain Peak | N 51.63624 | W -9.09277 |

Locations and classifications of the Rosscarbery group circles, and of other structures and features mentioned in the text. Reference numbers in the Archaeological Inventory of County Cork, Volume 1, are also provided (where applicable).

*

Table 2

| Townland / Name | Max. Height in Metres | Max. Width in Metres | Original Number of Stones | Central Stone | Outlier | |

| RC1 | Ahagilla | 1.35 | 7.00 | |||

| RC2 | Ballyvackey | 1.50 | 8.50 | 9 or 11 | ||

| RC3 | Bohonagh | 2.85 | 8.50 | 13 | ||

| RC4 | Carrigagrenane North | 1.00 | 5 | Quartz | ||

| RC5 | Carrigagrenane South | 1.10 | 8.50 | 19 | Yes | |

| RC6 | Drombeg | 2.05 | 9.00 | 17 | ||

| RC7 | Garryglass | 0.40 | 11 | Yes | ||

| RC8 | Glanbrack | 0.95 | 2.80 | 5 | NW-SE Pair | |

| RC9 | Knocks North | 1.10 | 8.90 | 11 | ||

| RC10 | Knocks South | 1.45 | 8.50 | 9 or 11 | Yes | |

| RC11 | Lettergorman | 1.40 | 2.75 | 5 | Quartz | |

| RC12 | Maulatanvally | 1.40 | 9.50 | 11 | Quartz | |

| RC13 | Reenascreena | 1.50 | 9.25 | 13 | ||

| RC14 | Templebryan | 2.00 | 9.50 | 9 or 11 | Quartz |

Morphological information for the Rosscarbery group circles including; maximum height of remaining stones, maximum circle width, estimated original number of stones and presence of a central stone, or outlier. If a stone is quartz, the fact is noted.

*

Table 3

| Townland / Name | Axial Stone Flat & Level | Axial Stone with Internal Bevel | Axial Stone with Northern Bevel | Radial Portals | Date Range for Construction | |

| RC1 | Ahagilla | |||||

| RC2 | Ballyvackey | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| RC3 | Bohonagh | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1371-1055 BC | |

| RC4 | Carrigagrenane North | Yes & Cup? | ||||

| RC5 | Carrigagrenane South | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| RC6 | Drombeg | Yes & Cups | 1115-791 BC | |||

| RC7 | Garryglass | |||||

| RC8 | Glanbrack | Yes & Cup | ||||

| RC9 | Knocks North | Yes | Yes | |||

| RC10 | Knocks South | Yes | Yes | |||

| RC11 | Lettergorman | Yes & Ledge | Yes | |||

| RC12 | Maulatanvally | Yes | ||||

| RC13 | Reenascreena | 1253-835 BC | ||||

| RC14 | Templebryan | Yes |

Morphological information for the Rosscarbery group circles including; axial top surface type, presence of a northern axial bevel and presence of radial portals. Radiocarbon date results are also provided where available.

*

Table 4

| 1500BC Declination | 1000BC Declination | 2000AD Declination | |

| Degrees | Degrees | Degrees | |

| Lunar | |||

| Northern Major Limit | +28.15 | +28.10 | +27.70 |

| Northern Minor Limit | +17.90 | +17.85 | +17.45 |

| Southern Minor Limit | -19.55 | -19.50 | -19.10 |

| Southern Major Limit | -29.90 | -29.85 | -29.50 |

| Solar | |||

| Summer Solstice | +23.85 | +23.80 | +23.45 |

| Winter Solstice | -23.85 | -23.80 | -23.45 |

| Equinox | +0.51 |

Declinations for the most commonly referenced solar and lunar positions, circa 1000 BC [28, 29].

Declination is the angle made between a heavenly body, or a horizon position, and the celestial equator, with the centre of the earth as their vertex. The celestial equator is a notional line around the sky (the celestial sphere), located midway between the north celestial pole and the south celestial pole. It runs from due east to due west, at an angle to the horizon that is determined by our latitude north of the real equator.

The heavenly bodies, such as the sun, appear to rotate around these celestial poles, in lines parallel to the celestial equator. Thus, from the perspective of a Late Bronze Age observer at a Rosscarbery group circle, the winter solstice sun would have set on a line that was separated from the celestial equator by an angle of -23.80 degrees. This angle was obviously consistent, regardless of the height of any hills underneath.

The contraction evident in all limiting declinations since the Bronze Age is due to ongoing changes in the Earth’s tilt on its orbital plane; the so-called obliquity of the ecliptic. The equinox value in the table refers to the midpoint between the solstices, if counted in days.

*

Table 5

| Townland / Name | Patrick Dec. | Patrick Az. | Ruggles Dec. | Ruggles Az. | Event to 1 Degree | |

| Degrees | Degrees | Degrees | Degrees | |||

| RC1 | Ahagilla | |||||

| RC2 | Ballyvackey | -4.00 | 261.50 | |||

| RC3 | Bohonagh | +0.88 | 268.28 | +0.60 | 268.00 | Equinox |

| RC4 | Carrigagrenane North | |||||

| RC5 | Carrigagrenane South | -31.20 | 208.80 | -30.60 | 210.00 | Southern Major Limit |

| RC6 | Drombeg | -22.68 | 227.33 | -23.00 | 227.00 | Winter Solstice |

| RC7 | Garryglass | |||||

| RC8 | Glanbrack | |||||

| RC9 | Knocks North | +1.22 | 269.83 | Equinox | ||

| RC10 | Knocks South | -27.95 | 214.00 | -27.80 | 215.50 | |

| RC11 | Lettergorman | -24.30 | 225.50 | Winter Solstice | ||

| RC12 | Maulatanvally | -5.14 | 256.67 | -5.40 | 256.50 | |

| RC13 | Reenascreena | -14.17 | 247.53 | -14.40 | 248.50 | |

| RC14 | Templebryan | -34.13 | 201.67 |

Mid-portal through axial orientation data for the measurable stone circles of the Rosscarbery group (declination and azimuth), extracted from wider collections by both Jon Patrick and Peter Freeman, and Clive Ruggles [30, 31].

Assessing the focal possibilities, or event indications, is not straightforward. The axial stones are wide and where portal stones have moved, or fallen, there may have been some difficulty in selecting a precise axis of symmetry. As a compromise between possible over-acceptance and under-acceptance of results, an error margin of one degree has been used. In addition, where the studies overlapped and varied, and a choice was required between values, the more recent data, by Ruggles, has been preferred.

*

Table 6

| Rosscarbery Group Results | Combined Group Results | Rosscarbery Results as % of Combined Results | |

| Range of Sample | 37.35 degrees | 48.20 degrees | |

| Number in Sample | 10 | 43 | 23% |

| Southern Minor Limit | 4 | 0% | |

| Southern Major Limit | 1 | 2 | 50% |

| Lunar Total | 1 | 6 | 17% |

| Winter Solstice | 2 | 3 | 67% |

| Equinox | 2 | 4 | 50% |

| Solar Total | 4 | 7 | 57% |

| Celestial Total | 5 | 13 | 38% |

Comparison of the Rosscarbery axial orientation results with the combined results from the surveys of Jon Patrick and Peter Freeman, and Clive Ruggles.

*

Table 7

| Townland / Name | Distance from Site 1 in Kilometres | Bearing from Site 1 in Degrees | Distance in Metres from a Line drawn from Site 1 to Site 2 | ||

| RC7 | Garryglass | 1 | 0.000 | ||

| Carrigfadda Eastern Peak | 2.963 | 133.736 | 4 | ||

| RC13 | Reenascreena | 5.856 | 134.438 | 63 | |

| RG3 | Tinneel | 10.009 | 133.822 | 0 | |

| RC3 | Bohonagh | 2 | 11.907 | 133.822 | |

| RC11 | Lettergorman | 1 | 0.000 | ||

| RG2 | Maulatanvally | 1.129 | 187.199 | 7 | |

| RC4 | Carrigagrenane North | 1.925 | 188.001 | 15 | |

| RC6 | Drombeg | 2 | 10.550 | 187.546 | |

| RG2 | Maulatanvally | 1 | 0.000 | ||

| RC8 | Glanbrack | 1.092 | 92.336 | 5 | |

| RC10 | Knocks South | 4.195 | 91.515 | 78 | |

| RC14 | Templebryan | 2 | 12.868 | 92.585 | |

| RG1 | Lettergorman | 1 | 0.000 | ||

| RC11 | Lettergorman | 1.742 | 196.821 | 14 | |

| RC5 | Carrigagrenane South | 2 | 4.251 | 197.267 |

To be thorough, it may be worth looking at whether some of these structures, rather than being positioned in individual, significant places, were combined instead into a larger structure, or gestalt. Over the ninety, or so, years since the publication of Alfred Watkin’s “The Old Straight Track”, a lot of people have attempted to find patterns in, or relationships between, the positions of similar monuments in a landscape.

Straight lines or astral maps have tended to be the most common templates. A selection of the tidiest straight-line results for the stone circles, and possibly associated stone groups, of the Rosscarbery area, are set out in Table 7.

In each case, a line is projected from the first site to the last, and the distance of the intervening sites’ deviation from the line solved by using the triangle between the two bearings. Thus, a straight track from Garryglass to Bohonagh might, theoretically, pass only four metres west of the cross on Carrigfadda’s eastern peak and go right through the stone group at Tinneel. Similarly, the two winter solstice circles of Lettergorman and Drombeg might be linked by a line that skims both the stone group at Maulatanvally and the circle at Carrigagrenane North.

There are a number of problems with this interpretation, however. All positional readings were taken by GPS, correct to 5 metres, and, consequently, the lines may be more crooked, or wider, rather, than those calculated. Contingent upon line-width, patterns, including straight lines of three or more points, might be formed in any sizeable random collection. Particularly if there are areas of thicker concentration.

Furthermore, although this analysis has excluded other elements of the Bronze Age monumental culture, it has included the stone groups and they may not have been a contemporary, or even a related, feature. Crucially, if deliberately placed, the monuments might be expected to indicate each other. If not for the sake of ritual necessity then at least for the sake of the future theorist. The only evidence of this latter is the rough indication from Lettergorman to Drombeg, via its adjacent quartz boulder and the stone group at Maulatanvally.

*

Notes

1. Walsh 1993, 104

2. O’Nuallain 1984, 44

3. Fahy 1959, 9

4. O’Brien 2012, 166

5. Fahy 1959, 16

6. Fahy 1961, 94

7. Fahy 1961, 97

8. O’Brien 2012, 167

9. Fahy 1962, 64

10. O’Brien 2012, 184

11. Fahy 1962, 61

12. Fahy 1959, 24

13. Fahy 1961, 94

14. O’Brien 2012, 259

15. Ruggles 1999b, 316

16. Ruggles 1999a, 107

17. Patrick & Freeman 1983, 51

18. Ruggles 1999a, 240

19. Ruggles 1999a, 217

20. Patrick & Freeman 1983, 52

21. Ruggles 1999a, 219

22. O’Rahilly 1946, 58

23. Graf 2004, 269

24. Graf 2004, 341

25. Graf 2004, 340

26. Graf 2004, 342

27. Trans. Brown 1997, 259

28. Freeman & Elmore 1979, 87

39. Ruggles 1999a, 57

30. Patrick 1983, 51

31. Ruggles 1999a, 217

*

Bibliography

Brown, C. 1997. Translation of ’Six Galician Poems’ in Federico Garcia Lorca : Selected Poems. Penguin.

Fahy, E. 1959. A recumbent stone circle at Drombeg, Co. Cork. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society.

Fahy, E. 1961. A stone circle, hut and dolmen at Bohonagh, Co. Cork. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society.

Fahy, E. 1962. A recumbent stone circle at Reenascreena South, Co. Cork. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society.

Freeman, P.R. & Elmore, W. 1979. A test for the significance of astronomical alignments. Archaeoastronomy No. 1 (Journal for the History of Astronomy No. 10).

Graf. F. 2004. In Johnston, S.I. (ed.) Religions of the Ancient World: a guide. Harvard University Press.

O’ Brien, W. 2012. Iverni : A Prehistory of Cork. Collins Press.

O’ Nuallain, S. 1984. A survey of stone circles in Cork and Kerry. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy Vol. 84, C, No. 1.

O’ Rahilly, T.F. 1946 (reprinted 1999). Early Irish History and Mythology. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Patrick, J. & Freeman, P.R. 1983. Revised surveys of Cork-Kerry stone circles. Archaeoastronomy No. 5 (Journal for the History of Astronomy No. 14).

Power, D. et al. 1992. Archaeological Inventory of County Cork. Volume 1: West Cork. Stationery Office, Dublin.

Ruggles, C. 1999a. Astronomy in Prehistoric Britain and Ireland. Yale.

Ruggles, C. 1999b. The orientation of Altar and other wedge tombs in the Mizen peninsula. In O’ Brien , W. Sacred Ground. Megalithic Tombs in Coastal South West Ireland. Bronze Age Studies 4. N.U.I. Galway.

Walsh, P. 1993. In Circle and Row: Bronze Age Ceremonial Monuments. In Shee Twohig, E. and Ronayne, M. (eds.) Past Perceptions: the Prehistoric Archaeology of South West Ireland. Cork University Press.

All photographs (c) Gordon J.R. Kingston

*

Reblogged this on The Heritage Trust.

LikeLike

Very interesting article Gordon

Skellig Foundation

LikeLike

Hi,

I am wondering do you live in Cork? My partner and I have moved to Reenascreena and I was looking to see if anyone would be interested in showing us this place with a little bit of the history. I am wondering would this interest you, or would you know of anybody? Thanks so much.

Áine

LikeLike

Hi Áine,

I do live in West Cork and I would probably have been ideal to show you around maybe 10 years ago, but not now; I don’t know what has happened but I haven’t the time to slow down any more. I would be happy to give you an idea of where to go via an email? Everything I did and saw around here was through reading books, following maps and asking permission to go on people’s property. And trying to make sense of it. It’s so long since I wrote that article; I think I’ve a list of useful texts at the end of it.

Best,

Gordon

LikeLike